Emblems of the Relationship Between Cuba and the United States

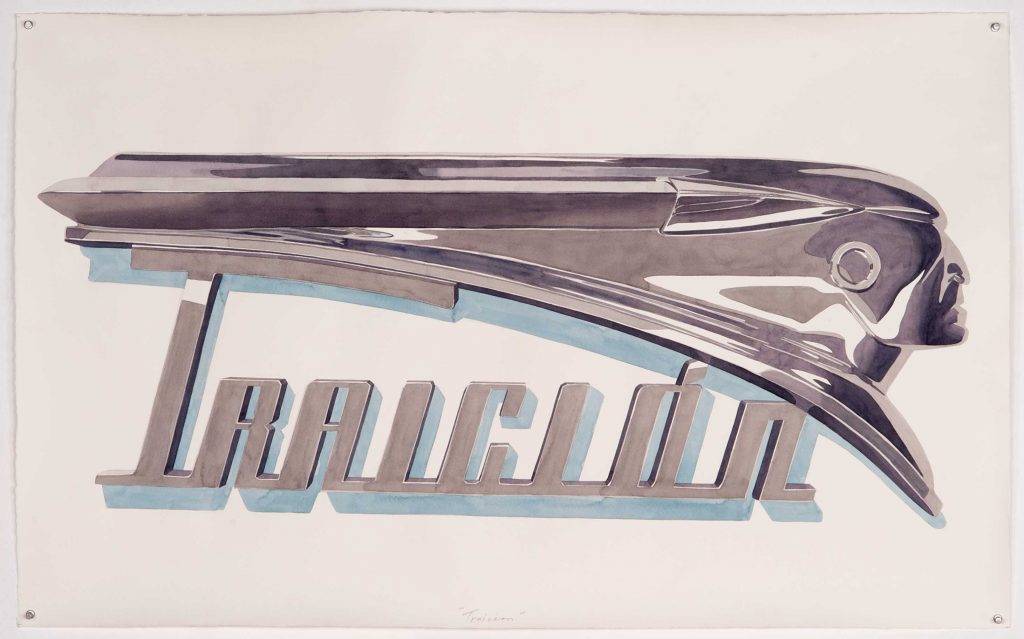

Initiated shortly after Fidel Castro’s death on November 25, 2016, in La Habana, the series Los Emblemas explores in all its complexity and its duality the notion of the emblem, under the prism of the Cuban historic, social and political reality. Metaphor of the relationship between revolutionary Cuba and the United States, Los Emblemas forms a cohesive ensemble of graphic works parodying logos of American cars from the 1940s until 1959, a vibrating echo of an almost disappeared world whose last traces of existence still remain in Cuba. Cuba’s love for American cars expressed itself in the maintenance and survival of these old-fashioned vehicles thanks to ingenuity of local artisans. Since 1959, Fidel Castro has prohibited the importation of foreign vehicles to Cuba or mechanical pieces to repair them, a manifestation of the United States’ embargo. Cuba has thus developed a unique and island culture, marked by great creativity. Instead of the famous motto that accompanies the logo of any car brand and connects the values and identity of the firm, the artist has chosen to place fake replicas of car logos by associating them with the twelve most quoted words of the Cuban Revolution. This collection of words is embodied in a rich set of popular typographies reworked by the artist, who came to constitute the meaning of the work. The resulting paradoxical meaning causes a real visual word game. Reflecting a strong antagonism between two visions of the world contained in a single object, each emblem offers a dual point of view on the conflicting reality that has passed through Cuban society in the last sixty years.

Los Emblemas’s Historical Matrix: An Entanglement of Meanings

Dagoberto Rodríguez had examined press news and the burst of Western newspapers that once again watched Cuba after the death of Fidel Castro. At this time, most of the dictator’s speeches were published online. The artist, mimicking the posture of the archivist, plunged into these discourses to draw up a hierarchy of the words the mostoften spoken during the revolution. He noticed that the words stated by Fidel Castro were the ones at the same time the most used in the revolutionary propaganda. Fascinated by the imagery of this “Revolutionary Gospel”, mistakenly strung from the Impact typography, originally used by the Cuban media, he extended his typographic research by borrowing from various popular sources to translate the Cuban revolutionary philosophy, crystallized in these archival documents and the design of the 1950s. This is the way Rodriguez brought to light the iconic Art deco typography. Iconic style of the inter-war period born in Paris and quickly spread to the United States, the Art Deco style appeared in 1930 in Cuba through historic buildings like the Bacardi building, colonial-era churches and hotels built up until the revolution in La Habana. Unfolding in all areas of visual arts, architecture, design and typography, this aesthetic movement was appropriated by Cuban culture with a pure lylocal Afro-Cuban influence under Batista as a political statement of “modernity”.

As for the American cars, the impregnation of the Art Deco style in Cuban architectural and decorative language attests Cuba’s unique position as the crossroads of different cultures, and its ability to assimilate and to mix these external influences into a fundamentally original style thanks to the skills of Cuban architects and craftsmen. Los Emblemas is a history of remixes.

Drawing by number 12

Historically, the Cuban revolution took place in a climate of great precariousness, in a country devoid of important economic resources. The revolution was done primarily by and through words. Rodriguez emphasizes the symbolic charge of language and its ability to become a true revolutionary weapon. Pronounced by Cuban leaders, they have turned the tide of events in Cuba, asserting the enforcement policy that has definitely rocked the fate of the Cuban people. Moreover, by choosing only twelve words, he encodes Los Emblemas series by superposing different meanings. The choice of the number twelve is a biblical connotation, that of the twelve apostles who spread Christianity. Rodriguez relates this religious allusion to the historical narrative of the Cuban revolutionary epic that intensely speculated on this biblical theme by relating it to the heroic figures of the twelve fighters who survived the first fight against the dictatorship of Batista during the Alegria battle of Pio,on December 5, 1956, alongside Fidel Castro. Beyond the fact, the number 12 is also a symbol of cosmic order, the number of space and time. It refers to an infinite and immutable time, where things arerepeated cyclically. The number 12 is an allusion to the division of time, in 12 months during one year, in two groups of twelve hours perday. It also refers to the number of zodiac signs in different cosmogonies.

Emblems as political weapon, emblems of consumption

The historical matrix of Los Emblemas istreated in a semantic perspective that emphasizes the dissonances between the signifier and the signified through an extensive research on language and typography and in favor of confusing linguistic operations.

Etymologically, but currently unusual, an emblem designates a work of marquetry ormosaic. This original sense denotes an immediate association with the craft sphere, as well as the decorative and ornamental dimension of the emblem. Currently, the term refers to “a visible symbol that represents an abstract idea”, associated with a motto, supposing a connection of more or less sensitive ideas and a certain system of values. Initially associated with the insignia of power – an obvious political connotation –, the emblem in the era of consumption becomes a visible support publicly enhancing the identity of a brand, a sign of social belonging and a decorative motif. Yet the work on the notion of the emblem, which has the peculiarity to associate a significant to a signifier, a word or a slogan with an image, which embodies it, has nothing harmless. Playing on the paradoxes inherent to the polysemy of this notion, Rodriguez recreates true conceptual images with a strong symbolic charge, by the confrontation in a single object of antagonistic values. Thus, the symbol V which unfolds in most emblems, was originally associated with the shape of the 8-piston engine of American cars, a symbol of power and strength. It becomes in Los Emblemas a reference to the political power. Behind each sign, each symbol conceals a deeper and more paradoxical political meaning.

Between Propaganda and Advertising

Finally, by questioning the constitution of the public media space and its system of values through the association of the marketing and consumption’s spheres with the one of politics, he proves to us that media and propaganda strategies are intimately linked to obtain adhesion or to support individual desire. The notions of propaganda and communication refer to realities of a similar nature, relating to the dissemination of information and the strategies that underlie it. The emblem became a vessel for cultural, social or political representations. By merging into a single object, hybrid and duel by nature, political and market values, he confronts Cuban identity from a cultural and political point of view by synthesizing two symbols of Cuban identity that are inherently antagonistic. While the American cars, symptomatic of the growth of consumer goods became the sacred icons of Cuban culture, he reveals the fascination of Cubans for a North American product. The words of the Cuban Revolution, a veritable moral guide of Cuban identity, are expressed in a radically inappropriate form, that of the North American car logos, by the recreation of absurd and antithetical emblems to the extent that they associate values apriori irreconcilable. Subverted by irrationality, logos became slogans in a game about the linguistic value of propaganda and advertising. The taxonomic order of Los Emblemas bypasses the viewer’s reason, perplexed by the irreconcilability of these encrypted works. This original approach evokes structuralism and its interest in the structures of language as well as conceptualism, parasitized by a political charge, emptied of its self-referential concerns in favor of a deep reflection on society, ideology and conflicts of power.

Reimagining Cuban Revolution’s Visual Identity

Icons of value, Americans cars were the result of a great industrial process, although they remain to be “unique pieces” for Cuban society that continues to customize them. These cars suggest a lifestyle where the past is a part of the present. They are associated in the Cuban culture with the pursuit of the freedom and define a real lifestyle in a country where the society cannot circulate freely. Paradoxically, the Cuban revolution did not seek to provide a definite aesthetic identity, and was never known for industrial or graphic design work, unlike the Russian Soviet regime imbued with socialist realism. As if to fill this gap in history, Rodriguez reinvents in a radically critical, ironic and subversive manner the design of everyday life that could have generated this revolution to support a new way of life and the advent of a new society. He highlights “this visual error of the Cuban revolution”, which did not prevent the advent of these luxury products from North America, in an ideologically hostile and anti-North American climate. These cars have survived as real cultural icons, typically Cuban. By conceptually linking the leftist and nationalist values of the Franco regime’s with the icon of American culture of the 1950s, they emphasize the historical contradictions experienced by Cuban culture. Not limited to cars of the revolution, Los Emblemas series will extend to furniture and objects of everyday life, to consumer goods inherited from the 1950s that still work today, including a series of refrigerators. The challenge of Rodriguez is to recreate, through a work on the border between conceptual art and design, this Cuban atmosphere so special where the past and the present are superimposed, by mixing the aesthetics of these reused objects with the philosophical ideas inherited from Cuban revolution.

Resistance and Memory: A Tribute to Cuban Recycling Praxis

In the words of Rodriguez, Los Emblemas is a work related to “resistance and memory” that unfolds as part of a narrative based on a rewriting of the history of design. Immersing into archives, he has designed this series of emblems integrally, inspiring from heterogeneous typographies and historical sources, hybridizing forms and updating them in a series of drawings executed on computer and then printing in 3D. Each piece is cast in bronze, copper then chromed, and sometimes painted. This interdisciplinary manufacturing process reflects a certain interest for the praxis and the know-how, by Rodriguez, who continue to claim the eminently artisanal character of his art. Starting from nothing, he builds step by step the artisanal pieces accompanying the entire production process. Material availability defines the manufacturing process and the shapes of the constructed object, hybridizing low-tech and high-tech technologies, harmoniously melt with various craft skills. He undertook to resuscitate the typography of American cars that had been lost by recreating it entirely, from coherent visual and typographical sources, playing on this state of confusion by a plastic work of pastiche and replica of a past time, revealing the stylistic typographical richness of this period of history. If this work could be qualified at first sight as archaeological and obsolete, the artist undertakes a real process of updating the slogans in our present time. He insists on the intensive practice of recycling which characterizes in depth the Cuban culture. Recycling is a daily process of life in Cuba that does not have a culture of consumption, but on the contrary an extensive culture of re-use, DIY, recovery and transformation of objects and buildings, constantly reused or reassigned, a phenomenon whose American cars are the perfect incarnation. In contrast to neocapitalist strategies of planned obsolescence, the process of symbolic recycling by the artist contradicts the consumerist paradigm associated with the West. He argues that in Cuba, everything is essentially eternal while questioning the notion of originality and simulacrum. Cuba is an ecosystem where everything is permanently recycled. In a way, Cuba has developed the absolute ecology of a world that no longer throws anything but that would begin to think that objects have a longer life than elsewhere. The lack of access to some food products, and the experience of daily energy shortages in Cuba partly explain this economy of recycling, improvisation and precariousness. However, this partially reductive explanation is underlined more subtly by Rodriguez with the springs of irony when he studies the unacknowledged fantasies associated with consumption in Cuban socialist society, subject to rationing and extreme control. For Rodriguez, craftsmanship is the symbolic source of the value of the work produced and recycling factor of the valuation of the object and its sacralization to the rank of a masterpiece.

By tracing the path of contamination of the visual repertory of Cuba inthe 1960s, the trans-historical issue proposed by Rodriguez in Los Emblemas takes place in the public space, through the confrontation of value systems, representations, ideologies, political models and social issues. The archaeological exploration of the textual and media strata becomes an unprecedented way to excavate answers about the complex identity of Cuba. Emblems of power, power to the people.

Jérôme Sans